Aden Crater, the Dying Place

(Please click on any photograph for a full sized image)

EL PASO, TEXAS – What do the mummified remains of an 11,000-year old ground sloth and this author have in common? We both have seen, in our respective lifetimes, the bottom of a huge volcanic fumarole in the middle of the Chihuahua Desert of Southern New Mexico, about an hour’s drive northwest of El Paso. I survived the experience, barely. The sloth didn’t. Aden Crater was our common ground, though separated by one hundred ten centuries of time.

This particular adventure began for me as a youngster in Boy Scouts, when our Troop 165 would take its annual “Aden Crater Weekend” camping trip out into the desert west of El Paso, off of what we called the “Strauss Road” (now NM AO17) near the base of the relatively recent volcanic formation. That formation is set within a beautiful landscape: wild grasses filling in the sandy swales between creosote bushes which yield the aroma of a Summer rain (known as petrichor), mesquite bush mounds, and various yucca and cactus species – outcrops of black and dark brown lava accenting the light brown patina of blow-sand covering everything except where plants, rocks or mountains protrude.

The Union Pacific’s main transcontinental railroad track between Los Angeles and New Orleans purposely skirts this area of volcanic “badlands” and that early route, carved in 1880 by the railroads around this difficult terrain within the Gadsden Purchase, is easily discerned from an aerial perspective. The sound of those trains rumbling by in the distance is the only thing that anchors a person to the present in this place, for the vast landscape has an ancient and timeless quality once you immerse yourself in the quiet solitude.

It was this general area of volcanic badlands, looking so much like the landscape of the Hawaiian Islands, that Marty Robbins immortalized in the ballad “El Paso“, with the line “...out through the back door of Rosa’s I ran…out to the badlands of New Mexico…”

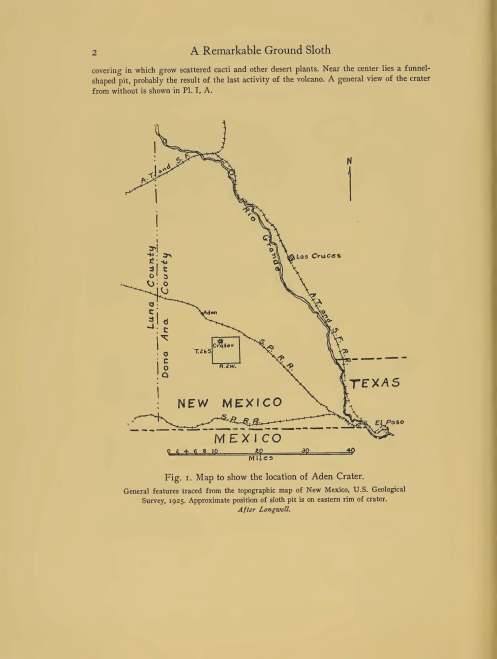

Aden Crater sits up above the sand hills and broad expanses of lava beds that form its skirts. The crater had belched out a huge amount of lava eons back, some 30,000 years ago according to the geologists. Those lava fields flowed from this, and several other, volcanic crevasses in the region during an active historic period which could have been witnessed by America’s first native inhabitants. Later generations would memorialize their history and record their passing by etching petroglyphs on the same dark surfaces of those ancient volcanic stones.

The timelessness of the area lends a magical quality to musing over these histories around an open air campsite as sparks drift into the starlit sky from a sweet mesquite-wood fire. In those ancient times that our Native American predecessors knew, this region had more rainfall and a different ecosphere than today. Grasses waved in the winds, trees dotted the landscape and a virtual savannah spread out across the horizon. The wildlife was also different than we see today. Grazing animals abounded, and ground sloths sauntered along poking for termites and grubs and other food their digging skills could excavate.

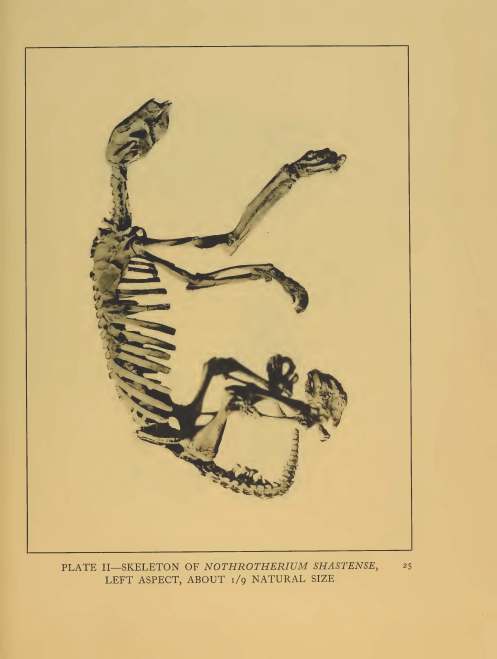

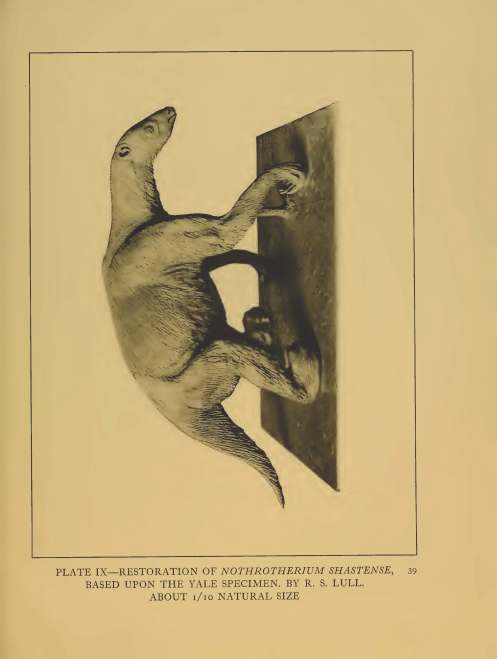

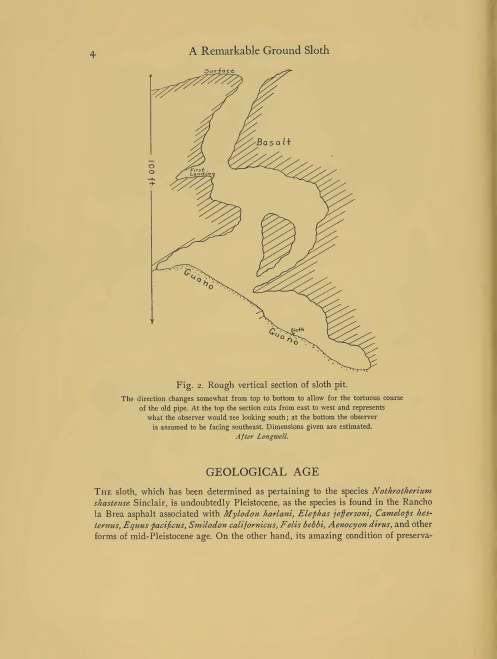

One particularly unlucky ground sloth some 11,000 years ago found the newly-formed volcanic prominence of Aden Crater enticing and wandered up and into the formation, eventually sniffing and snooping its way over to the rugged southeast wall of the crater where it thought the gaping maw at the mouth of the large fumarole cavern looked inviting. Unfortunately for the sloth, the fumarole presented too steep an adventure for his climbing skills to handle. Either the ninety-some-odd-foot fall to the bottom or his inability to extricate himself after that fall led to to the sloth’s demise, and he was preserved on a large mound of bat guano at the bottom of the cavern for discovery 10,000-odd years later by a team of explorers from the Peabody Museum of Yale University in August of 1928AD.

A 1929 report was published by Yale University Press and, henceforth, generations of Boy Scouts have learned this story, a genuine tragedy in natural history terms, which played out within this grand landscape long before the arrival of modern man.

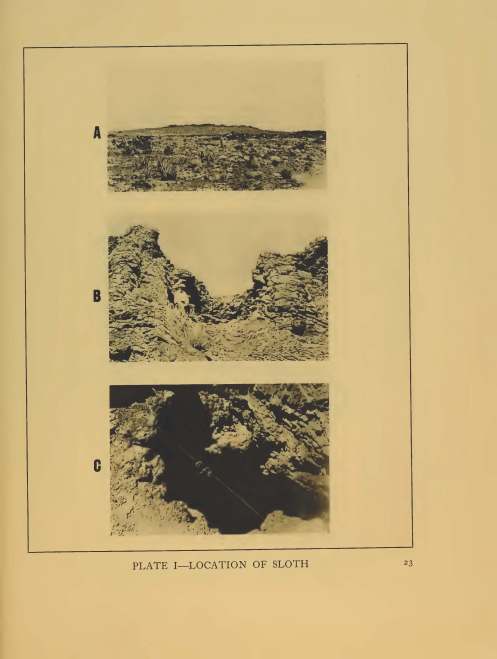

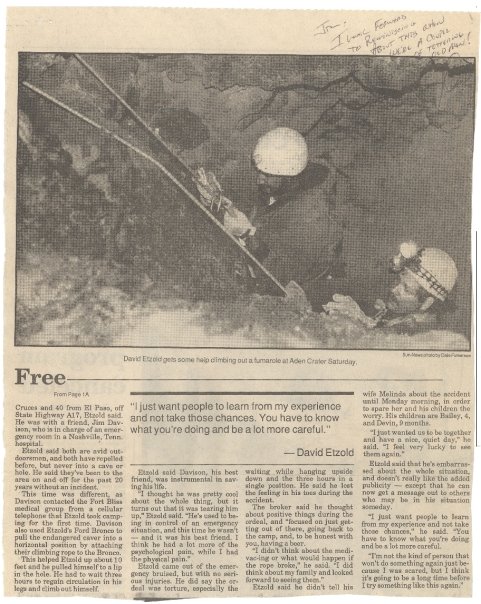

For reference here, the photographs on Plate I (above) are described as follows: A) Aden Crater seen from a distance; B) The “notch” that marks the location of the fumarole on the southeast rim of the crater; and C) The mouth of the fumarole opening just outside of the southeast crater rim.

What a story! What a discovery! How in the world could a group of young Scouts NOT be intrigued with such a tale? It was always one of my favorite camping trips in Boy Scouts. But, we never saw the inside of this awesome cavern, and that haunted me. It took 25 years or so, but in 1991 this former Boy Scout made that sloth and the volcanic fumarole the purpose of one of the first expeditions ever undertaken by the International Natural History League (INHL). This is how it was:

I had been married only seven years, Melinda and I had two small girls at home in our our old Kern Place neighborhood when the Executive Director of the INHL, Dr. James Davison (a life-long friend who now lived in Nashville), flew into El Paso for one of our regular adventures, this one planned around Aden Crater. This expedition, however, proved to be a rather irregular adventure…as you will soon see.

The Ford Bronco was loaded with our camping gear, that new-fangled cellular “brick” phone I had recently acquired for my real estate work was charged and the cooler was full of food and drinks. The rutted dirt road paralleling the Union Pacific railroad tracks out past the Santa Teresa Airport and then past ruins of an old frame home and corral – what had been Strauss, New Mexico – carried us into the wild wide open spaces of Southwestern Dona Ana County. The terrain was familiar to us, having grown up taking many camping and hunting trips out into these areas all of our lives. The music from the car stereo was cranked up, and the dusty plume behind us trailed off into the distance toward El Paso.

We were looking forward to using the climbing equipment that I had been practicing on with other friends, Vic Kilstrom and David Malin up in the Franklin Mountains, and Jim and I wanted to see if we could finally get down to the bottom of that famous fumarole. Several times we’ve camped at Aden Crater and hiked to the edge of its maw, but never had we attempted a descent. Ropes and climbing had been something that I had tried occasionally (along with spelunking) while attending the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee back in the mid-seventies. I liked the thrill of a long rappel drop off a big cliff. This would be cool.

Soon the dirt road was crossed by the first of several spines of lava rock that the road engineers failed to remove from the roadbed. These “speed bumps” were a signal that the crater formation was approaching and the turn off to the left would be past the last such lava spine in the road. Before long, a meandering narrow sandy roadbed took us off to the south and wound back behind and up into the actual volcanic crater itself. I was glad we had a high-clearance four wheel drive vehicle. There, inside the crater, we found a nice flat niche up against a lava cliff for our campground and we spent the afternoon setting up camp – enjoying the pristine air, landscape and sky.

A quick hike around found some of the “shrink cracks” that formed narrow deep canyons within the crater. Along the upper ledges of this canyons, huge white owls lived and the bones of their prey left telltale signs on the rocks below. The view off to the horizon seemed endless.

It is a wondrous place. Giant blocks of lava, black and brown colors thrown up and around by forces too massive to even imagine. Golden grasses now filling in the low spots and flat areas, wafting in the almost constant desert breeze from the West. The sky that night lit up like a light show, stars so bright they looked like a million pinholes in a black sheet stretched in front of a blazing fire. We talked and drank late into the night, but each of us had a bit of a queer feeling in our gut about the task ahead the next day.

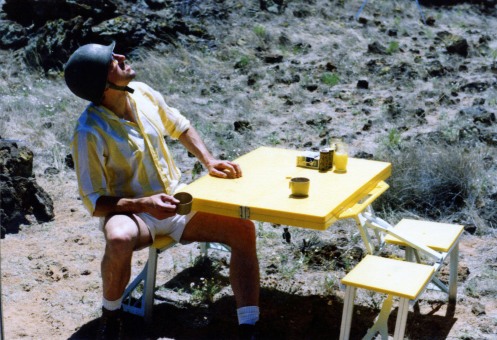

Morning dawned early, the crisp high desert air refreshing, as we rousted from our cots under the tarp we had set up. A hearty breakfast, one good check of the climbing gear, and we’d be off to the southeast rim and the yawning maw of the fumarole. Jim borrowed a Korean War era helmet of my father’s to protect from being beaned by loose rocks. I couldn’t help but be amused at the sight of Dr. Davison with that helmet on, as if we were going into battle!

We referred to the diagram of the fumarole drawn by the Peabody-Yale Expedition of 1928 to orient ourselves for the descent. One long climbing rope, a sit harness, a custom made rappelling descender, two Jumar ascenders, heavy leather gloves and a good dose of confidence were the tools for this adventure. The descender we had used often up in the Franklin Mountains in El Paso. We had practiced with the Jumars on the short cliffs next to our campsite and had a feel for the system. The Bronco with our cell phone (the “brick”) stayed at the campsite, and we packed our equipment, cameras and supplies over to the fumarole by foot. There, looking into the black hole, we could feel the steady rush of cool air coming out of the earth…a sure sign of a deep cavern below us!

I went first, dropping the rope into the opening, and hooking my brake bars of the descent equipment into its strong fibers. Before slipping over the edge, I made a seemingly random off-the-cuff comment to Jim’s video camera: “If I don’t make it, I love you Melinda!” How ironic that would be to watch later! Putting my weight on the rope and leaning back over a precipice is always the hardest part of rappelling. Once I was over the edge and inching myself down, the passage slipped away to my right at about a 45-degree angle until coming to a place where I had to crouch and peer over the lip of a hole in the floor down into the main chamber. With my flashlight, I could not see the bottom. This was going to be intense!

Dropping through that hole and down into the large cavern, the walls quickly receded and I was dangling on the rope – slowly spinning around with no wall to stop the rotation. I could yell up to Jim, far above it seemed, but our voices were muffled by the angles of the chambers I had just passed through. Slowly, I allowed the rope to slip through the descender as I lowered myself into that dark chasm, aware of the musty smell of bat guano in the air and noticing the slight echo of the sounds I was making. Eventually, I landed on a solid flat platform of rock where I stopped and stood up, gaining my composure and deciding that this would be a fine spot to wait for Jim’s descent.

Off came the harness and up went the rope and descender equipment to Jim, waiting at the top. Soon, I could hear Davison coming down the passages above, then I heard him above me on the edge of the hole at the top of the huge cavern. Within a short time, and with a lot of banter between us, Davison was by my side and, in wide eyed excitement, we slapped a celebratory high-five. Now what?

As any good adventurer usually decides to do in a moment like that, Jim pulled out his video camera and started filming us in infra-red. There wasn’t much to say, we were both hyperventilating and our pulses raced. Words would get caught in our throats and the musky air made it hard to catch a deep breath. A little posed conversation for the video, and soon we attacked the real issue: Do we go further, or call it a conquest? I must say, I was rattled. That last descent, with no walls for stabilization, was a real feat. Thinking of climbing back up it on the Jumars was daunting to say the least. I voted to call it a success and not risk further descent. There was no telling how long it might take to get out.

We only had the one set of climbing gear, so one of us would have to ascend and then throw the equipment back for the other to use. Who would go first? I’m not sure to this day whether there was a conversation on the subject, or whether Jim volunteered to go out first since I went in first. No matter, it was Providence that looked over our shoulder on that decision. Jim strapped on the harness, got out the Jumars and attached the clamps to the rope, one above the other about chest high as the rope dangled to his feet. From those Jumars hung two rope stirrups into which one places each boot.

The process is to stand in the stirrup, where your weight on the clamp presses it against the rope, pushing with that leg and with the corresponding hand holding at the clamp until the other boot presses into its stirrup and its clamp grabs the rope where your other hand holds as the other leg pushes up and the hand releases its clamp to move up another foot or so. The hands and boots move sequentially up the rope in this way, clamping and releasing, moving up, clamping and releasing, moving up. Spinning around on that thin strong rope while executing this process adds to the tension and increases the strain. We did not have a “sit harness” with a carabiner and separate Jumar ascender clamp that would have allowed us to pause, sit with our weight on the third Jumar, giving our legs a rest. Lesson learned.

Jim made it to the hole in the floor above and, with noticeable grunts and groans, heaved himself over the ledge onto the “First Landing”. Soon he was out, and with a very faint shout, down came the rope and harness and Jumars. My turn.

I can remember doing something as I put on the equipment that I had never done before. I had extra boot laces, quite a bit actually and, as I was carefully putting each boot into the stirrup of its Jumar, I took the extra boot lace and tied it securely around the stirrup and each ankle…so I couldn’t step out of the loop of the stirrup as I climbed. Then it began.

Each step was a physically and mentally exhausting process, a balancing act and a crushing push to move the clamp up in sync with the corresponding boot. One, two….one, two….all the time, spinning around as the rope disappeared into the inky darkness above. It was hard, but I finally made it to the ledge above, that shelf of rock where the tunnel headed off in the 45-degree angle and where there were walls, and a floor!

Now, I just had to get those two clamps up and over the rock ledge. Knowing I would need some movement room, I got each clamp up against the other, my hand clenching one above the other. Since all my weight was on the rope, and the rope was taught and running over the face of the ledge, I’d needed a way to get my weight off the rope for a split-second in order to get the clamps up the rope and over the ledge…there was no way I could push the clamps up the rope and over the ledge with all my weight on the rope. How do you do that while hanging on the rope you need to get off of?

All I could think to do was to hop. So I hopped. I hopped again. When I hopped, I’d push in sync with both legs and hope that the rope would slacken enough to be able to push the clamps up and over the ledge. Then, on a third attempt, I pushed with both legs hard and hopped again, and for a moment it seemed to work….and then the rope slapped back against the rock with my full weight…and my grip on both clamps was sprung by the force of the impact of my knuckles with the rock and the Jumars. I hung there, standing in the stirrups, balanced for what seemed forever ….and then I fell backwards, my nails clawing at the rock ledge as I flipped upside down. The stirrups caught my boots at the ankles, I snapped to a bouncing stop, swaying in that huge dark chamber….upside down!

My hat and several things from my backpack fell out. My arms dangled above my head, pointing to the dark bottom of the cavern. I took a breath. I was still alive. What a feeling….that few mili-seconds between when the fall began and actually happened seemed like ultra-slow motion replaying it my mind. The stirrups saved me. That little voice that whispered to me to use my extra boot laces to tie the stirrups onto my ankles saved me. For now, that is.

I was hanging upside down in a dark, huge chamber, no walls to touch – much less see – and filled with bats. I yelled out to Jim. He could barely hear me. Finally he understood, and I could sense his anguish. There was an urgency to his instructions to keep my head up and to manage a way to prevent blood from pooling in my brain. Right, that made sense. I won’t die from a caving fall, I’ll die from a stroke…induced by the pressure of blood on my brain! Not this guy.

So, I tried being an Olympic gymnast, and pulled myself up the rope to my feet. Surely, if they could do this on the rings I could, too. Not in this life! I was only able to get my head and shoulders up to about my waist height, into an “L” shape, where I could hold onto the rope and let my heart pump some of the blood up to my legs and feet. This was painful, and I could only hold that position for so long. Maybe a few minutes of this position at a time was all I could muster, and then I’d have to let go and drop upside down again to rest and catch my breath. This went on for some time…a long time.

Jim, in the meantime, had rushed back to the campsite where he found the car keys. Thank God I had not taken them with us on the cave expedition! He also found the cell phone and grabbed it…a bad signal, maybe better at the crater rim. I think the Bronco was never the same after Jim’s drive out of the crater and cross-country through the lava ridges along the flanks of Aden Crater over to the entrance to the fumarole. He made it, and the car was still running, suffice to say. He yelled down to me that he was going to attach the trailer hitch to the rope and try to haul me up with the car. In a minute I felt a tug, then another, and another and I seemed to move up some…enough to get me wondering what I’d do when my feet and legs made the rock ledge first. They were getting numb and beginning to ache. Not to worry. The tugs stopped, and Jim was soon yelling down to me faintly that the rope was fraying on the sharp volcanic rocks…badly. He had to stop, fearing the rope would break. That felt bad.

I had been furiously pulling myself up hand over hand to a sitting position for an hour or so. I was exhausted and my hands hurt, even though I knew I had gloves on. Maybe blisters were forming, in fact, that was very likely I thought. Great. Now what? This was serious.

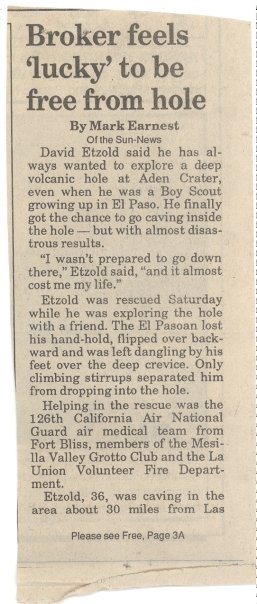

Jim now had pulled out the cell phone and was trying to reach the “911” service to get emergency help. The signal was bad, intermittent at best out in the desert so far. No telling where the closest cell tower was in those days. The 911 operator transferred Jim to Fort Bliss Army Air Defense Center, our huge base right in the middle of El Paso. The thought was that they had a Med-Evac Helicopter that might be able to help. No, that wasn’t such a great idea. Call transfer after call transfer, Jim was on hold for what seemed like an eternity. The battery power was draining fast on the cell phone and we had no car charger. Finally, a young officer got on the line who seemed to know something. There was a problem, though. Just a few months earlier, the main Med-Evac squadron at Fort Bliss had been transferred to Saudi Arabia to prepare and execute Desert Storm. The crews at Fort Bliss now had been called up from the Army Reserves, and they were new to the area and mostly from North Carolina. They were lost trying to find Aden Crater on a map…and in the field from air, as dark descended….well, spotting a parked Bronco truck in the middle of the Chihuahuan Desert was a stretch. As Jim was just finishing his explanation of where we were, the battery went dead in the cell phone.

Down in the cave, I knew nothing of this. All I knew was that it was getting on two hours and I was hurting pretty badly. That ache in my legs and feet was more pronounced, and my arms and shoulders were cramping from the rope work. My hands felt like the palms were burning. My head hurt, it was hard to take a deep breath and I needed to pee. Yes, I needed to urinate. Imagine, there you are, hanging upside down, bladder telling you that you needed to void pretty soon. What would any good Boy Scout do? Take a piss, of course…so, I carefully arched my back as far away from vertical as I could, opened my fly and let loose as hard as I could…hoping to not have a missed shot. Just for good measure, I clenched my mouth and eyes shut as hard as I could, it seemed to help….and soon I was relaxed again…at least as best I could be under the circumstances.

Jim yelled down to me that he had reached Fort Bliss and a helicopter would be on the way. I needed to hold on a while longer. Good…some hope. I had not had a lot of that down there and was on a rather sobering prayer cycle with Jesus. It’s interesting looking back on what you ask for in prayer at moments like those. Only here, those moments went on, and on, and on, and on…interspaced with the serious work of pulling myself into a situp position again.

Three hours or so, and I heard the whoop, whoop of helicopter blades descending. They had spotted the truck next to the hole and were landing right there above me on the edge of the crater! God, thank you! I yelled. As the engine noise died down I could hear people yelling down at me. Faintly it sounded like “Hello, are you alright?” Really? You’re kidding? Hadn’t Jim told them anything? I yelled back something less polite, pretty aggressive, along the lines of get me the frack out of there! There was more yelling and commotion that I couldn’t discern, and then a strong new voice yelled down…”Sorry sir, we don’t have any ropes or rescue equipment…we’re going to have to call in some other help.” What? No….no….no! I can’t take it! You’re kidding? No rescue equipment on a Med-Evac helicopter?

That was the worst time. I was nearly done. My hope was fading, my body hurt terribly, my hands could hardly hold the rope to pull me up to waist height any more. As far as I knew, if my brain burst a blood vessel I’d get a shrieking headache and pass out. Maybe that was best, though. I relaxed and hung there. It seemed like a long time passed. Some energy inside me helped pull that body of mine up that rope every few minutes. I was dead. No, I was a zombie. This was a dying place. I was face to face with Death for the first time in my life.

Take me fighting, or never take me! I won’t be that easy, Mr. Reaper…you’ll have to work a little harder. Thoughts of my children, who would never really know me…and my sweet beautiful wife, Melinda, who would wonder how this stupid thing happened…all crossed my mind. Then, I thought of Jim…poor old friend, how could he come to terms with seeing his best friend dangle to death out of his control? He’s an emergency room doctor, but couldn’t help his best friend? How would he live with that? How could he tell Melinda? Time seemed to creep to a halt. I felt woozy.

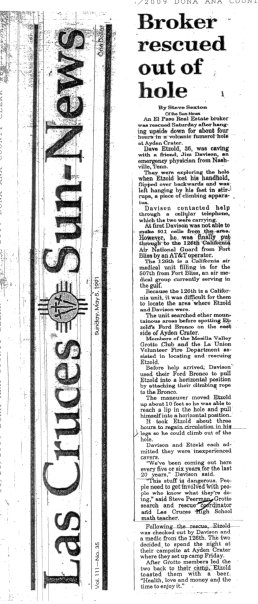

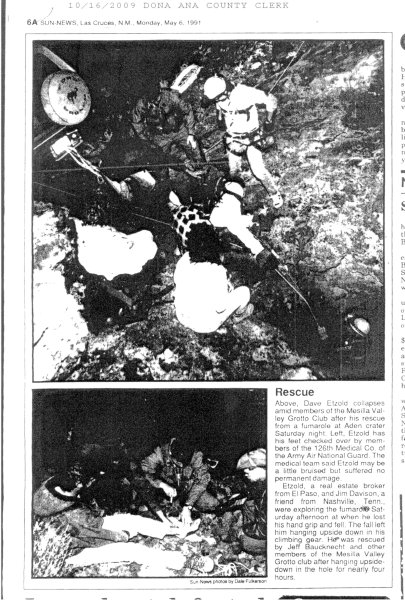

Then, a shout from above! What was that? Another shout…yes, I’m still here…get me the frack out of here! It was, as it turned out, a Mountain Rescue Team from Las Cruces (the Mesilla Valley Grotto Club) that usually works the Organ Mountains for hikers stranded and hurt. They had been called by the State Police, who had been called from the helicopter radio by the Med-Evac Team. Down they came, though it seemed like another hour it was only half that time before they were at the rocky ledge above my feet, and three strangers/angels were giving me encouraging support and slowly pulling me up by the rope …to finally be dragged across that sweet rocky ledge and be able to lay out flat! My legs were dead, I couldn’t feel them, numb and painful at the same time. My feet and ankles, though numb too, hurt like they had been crushed. My shoulders and arms were blazing with pain and my hands were like pulp under the shredded fragments of those leather gloves. But, I was alive…

They wanted to strap me into one of those rescue stretchers, but I refused. Please let me just wait a minute and restore the circulation in my legs…I want to walk out on my own…please! Half an hour or so later, after several bottles of water were guzzled and a granola bar chewed for energy, I took my first step in five hours. One rescuer in front and two behind, I slowly emerged to the surface. Spotlights, flashlights and camera flashes greeted me, as I fell on my knees and kissed the ground! There was a crowd there…and a reporter from the Las Cruces Sun. The helicopter crew still was there to make sure all went well. Back slapping and cheers went round and round. Jim came up and gave me the biggest hug he’s ever given me…and I knew where it came from. It was over. I lived!

Before everyone, I turned to the Rescue Crew chief, handed him my ropes and climbing gear, and said “Here, please take these as a donation…I’m not doing ropes again!”

I invited the crew, rescuers, reporters, Army guys and all, over to the campsite for a beer. They couldn’t believe it. Yes sir, let’s tip a cold one together tonight boys…for tomorrow I’ll wish I had. About eight followed us over the rocky trail back to camp, where Jim popped the tops of several six packs for everyone…my fingers couldn’t do the pop-top, so Jim insisted. My good doctor friend slipped me several good pain pills as goodbyes were said, and I curled up in my sleeping bag knowing that the morning would have its own surprises, but thankful to God for delivering me that night from an awful experience.

Melinda and I talked about it quietly, and alone after I got home Sunday. I couldn’t use my hands, nearly all the skin was gone from their palms. She gently washed my hair for me the next day in the kitchen sink before I went in to the doctor’s office. Within a few weeks, it was all just a horrible memory.

Today, though, I recognize it as a second chance. We don’t get many of those…I’m taking this one quite seriously.

_______________________0__________________________

EPILOGUE

Years later, I have returned to Aden Crater and looked down that hole several times. My son, Liam, who would never have been born had that day in May 1991 taken a different turn, was with me on one of the more recent trips back. So was my son-in-law, Joseph Perry, a Captain in the US Army and married to my oldest daughter Bailey. They know it was a major event in my life. We talked about it all the way out there, within the crater, and on the way home. Events such as this are etched in ones memory forever, crystalline sharp. It is still very real and personal in my recollection for this blog post. Only I know how close the story came to ending that day, though. I faced Death and I now fear not.

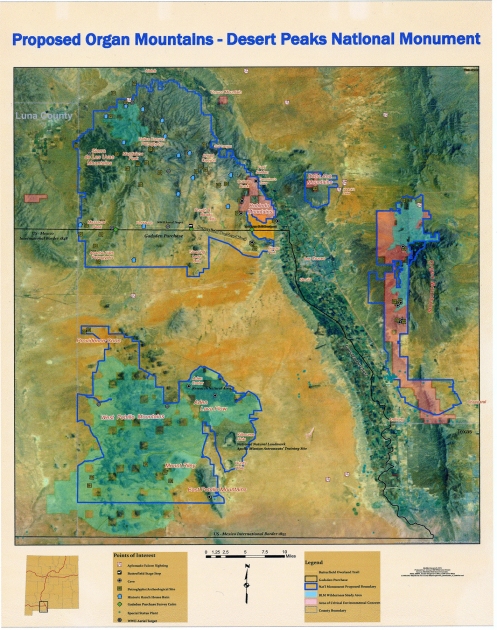

Recently, on May 21, 2014, President Barak Obama signed a Presidential Proclamation designating 500,000 acres of remarkably beautiful land in Southern New Mexico as the “Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument”, the boundaries of which include some of the most interesting geologic and historic locales in my favorite playground of a state. Aden Crater and its surrounding lava fields, the original “Badlands of New Mexico” per Marty Robbins, is now part of and protected as a National Monument.

A link to the site for the actual Proclamation creating the “Organ Mountains Desert Peaks National Monument” on the White House website:

Great story and glad that you’re ok! Thanks for sharing. I made my first trek to Aden Crater when I was 5 in 1989. I remember my parents talking about this from the newspaper. Even odder that Joe was my squad leader while we were at West Point! Hope all is well with your family!

Wow wee! What a scary adventure. I was at the edge of my seat the whole time l was reading your incredible story. So glad you are here to tell about it.

Incredible! Hair raising to read. Just as glad now I never did know about he other two “holes”, Kilbourne and the one further south.